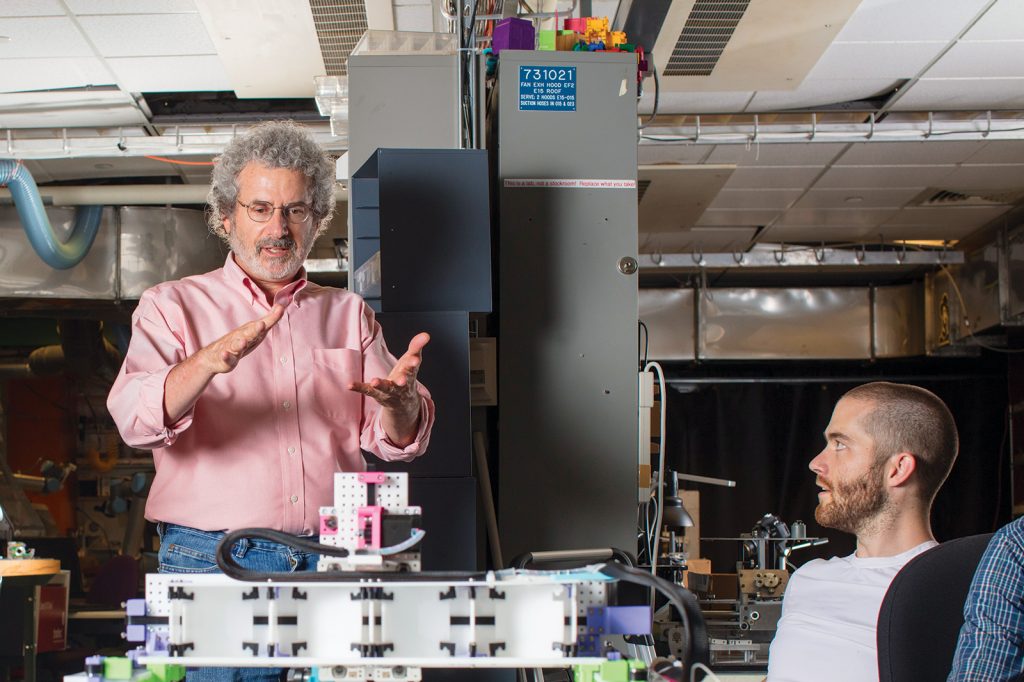

Neil Gershenfeld outlines the impact of fab labs

NEIL GERSHENFELD HAS BEEN CALLED THE INTELLECTUAL FATHER OF THE MAKER MOVEMENT. He’s spent more than a decade bringing the means for invention to remote corners of the globe via fab labs—facilities for custom-producing objects through digital fabrication (the umbrella term for computer-controlled manufacturing processes). Spectrum asked Gershenfeld, a professor of media arts and sciences and director of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms, about the growing popularity of fab labs— a topic he explores further in Designing Reality, a book he co-authored with his brothers, Alan and Joel.

How did fab labs get started?

NG: I teach the perennially oversubscribed MIT class How to Make (Almost) Anything (MAS.863). This started modestly to train users of the Center for Bits and Atoms’ digital fabrication research facility, and subsequently grew to add shop sections through the Department of Architecture, then the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and then Harvard. Inspired by what the students were doing in the class, and by the analogy with the history of minicomputers (which came between mainframes and PCs), my colleagues and I developed fab labs as an outreach project for the National Science Foundation. We put together a package of the most-used tools and processes from our shop to take into the field, including 3-D printing, scanning, and design; laser cutting, machining, molding, and casting; and electronics production, assembly, and programming. Fab labs today, like minicomputers a few decades ago, cost about $100,000 and fill a room. That cost is coming down as the equivalent of PCs for fabrication emerge, and also going up as regional super-fab-labs appear.

Where are fab labs located? How are they used?

NG: The first fab lab was started in Boston in 2003 with community pioneer Mel King at the South End Technology Center. The number of fab labs has been doubling ever since, approaching 2,000 now (this scaling has come to be called Lass’s Law, after Sherry Lassiter who manages the program). They’re located from the top of Europe to the bottom of Africa, and from inner cities to rural villages. They are, of course, used to make things—projects range from furniture to whole houses, from circuit boards to computers, from skateboards to drones, and from kitchen utensils to aquaponic systems. But in many cases, the act of making is itself more important than what’s made. Fab labs are used to teach classes, incubate businesses, build community, reduce conflict, and create infrastructure. To support these activities, we’ve spun off programs including a Fab Foundation for operational capacity, a Fab Academy for distributed hands-on education, and Fab Cities for urban self-sufficiency.